FOALING A MARE: From the water breaking to foal’s first hours

*** This article is intended for informational purposes only and should not be considered a substitute for professional veterinary advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a qualified veterinarian when dealing with foaling complications or medical procedures for mares and foals. While the author has shared their personal experience as a foaling professional, the actions described require extensive training and should only be attempted under the guidance or presence of a veterinarian or qualified foaling expert. Improper handling during foaling can result in serious injury to the mare, death of the foal, or long-term health complications. Always prioritise professional veterinary care.

I learned to foal mares in a well lit stable bedded with straw. The justification for straw over other bedding was that straw is usually a deeper, softer, warmer bed and it won’t stick to a newborn foal as much as shavings and newspaper might.

Most mares will give indications that they’re about to foal. This might include walking the box and even a box-walker will get more driven in their walking when they’re foaling, if this is one of their symptoms. Sweating, but some will only sweat a little or even not at all, and some will be dripping. A full bag (the teats) and milking or waxing. The bag can be “full” for weeks and go back and forth between full and almost full. The mare could wax for a week before foaling or for only a couple of hours before, or not at all.

But the most important thing is that not all of them present with these symptoms, so although they’re a fairly good indication they can’t be relied upon.

More accurate, but subtler indications, are that the vulva will loosen and lengthen just prior to foaling and the slope of the croup will drop to flat or almost concave.

My Foaling Kit:

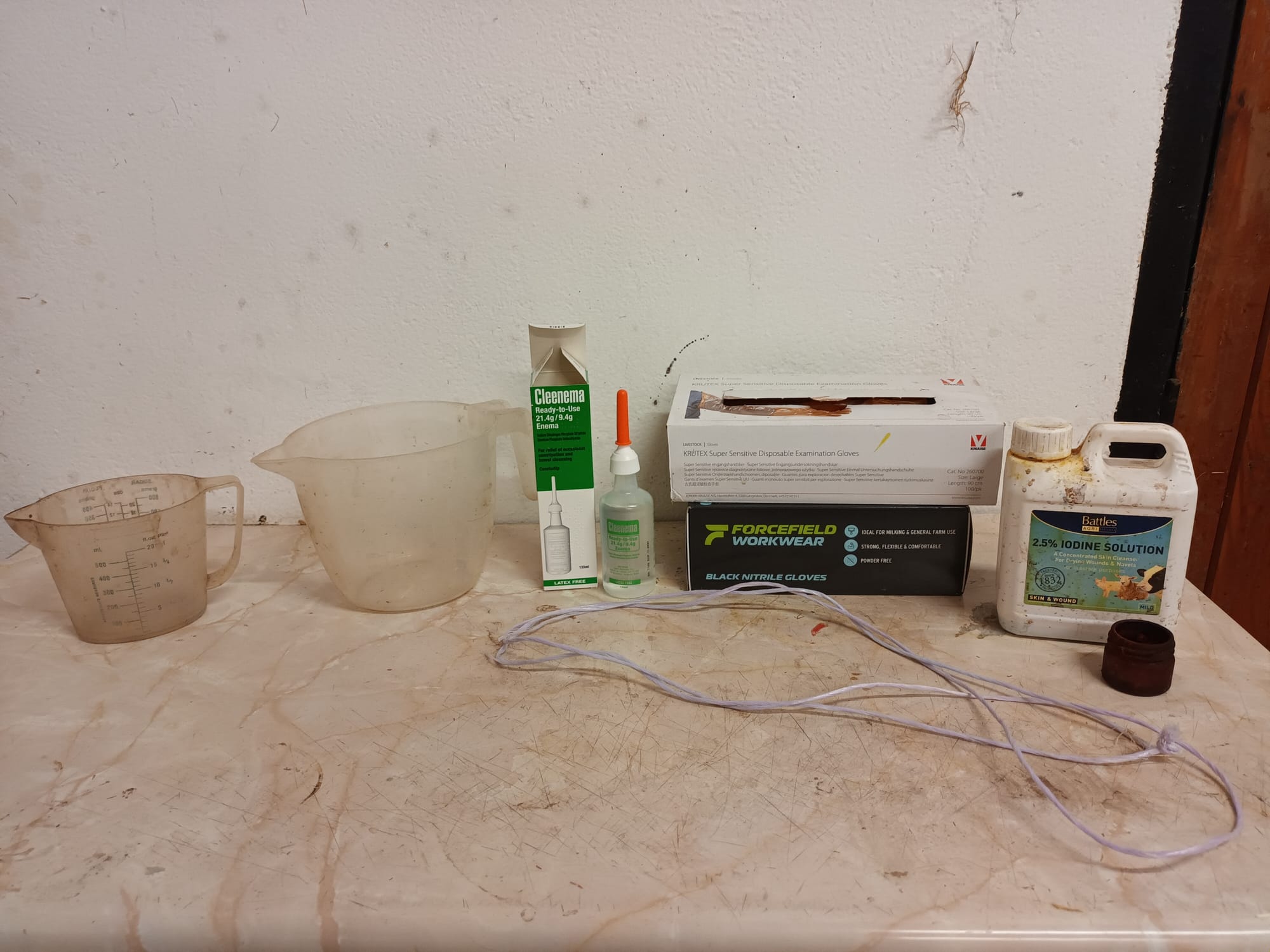

For the foaling itself, I always gather the following items:

- A piece of twine about 1m long (you can cut them a little shorter, but I prefer to have plenty to play with, so to speak – the twine from small square bales is perfect).

- Iodine liquid in a tiny little jar.

- A shoulder-length surgical glove.

- A short disposable nitrile rubber glove.

- An enema (they come in pre-prepared bottles).

- A measuring cup filled with warm water (it doesn’t have to be a measuring cup, but a container of at least 1.5L)

- A measuring cup filled with cold water.

Once the water breaks, the mare is about to foal. The water breaking can look a little like they’re urinating, but they won’t take the traditional “pee-stance” to do it and I’ve always found that there’s a smell specific to a mare’s water breaking.

This is the point where I fill up the measuring cup with warm water, unbox the enema and put it into the warm water, making sure that the whole thing is covered, fill my little jar with iodine, fill the other measuring cup with cold water and prepare the tetanus shot. Bandaging the mare's tail is not required, and we’ve never done it, but all the YouTube videos I’ve watched have demonstrated this practice.

I also call for a second set of hands. Just for safety, especially when you have a maiden mare (a mare who has never had a foal before). This person should also be someone with foaling experience.

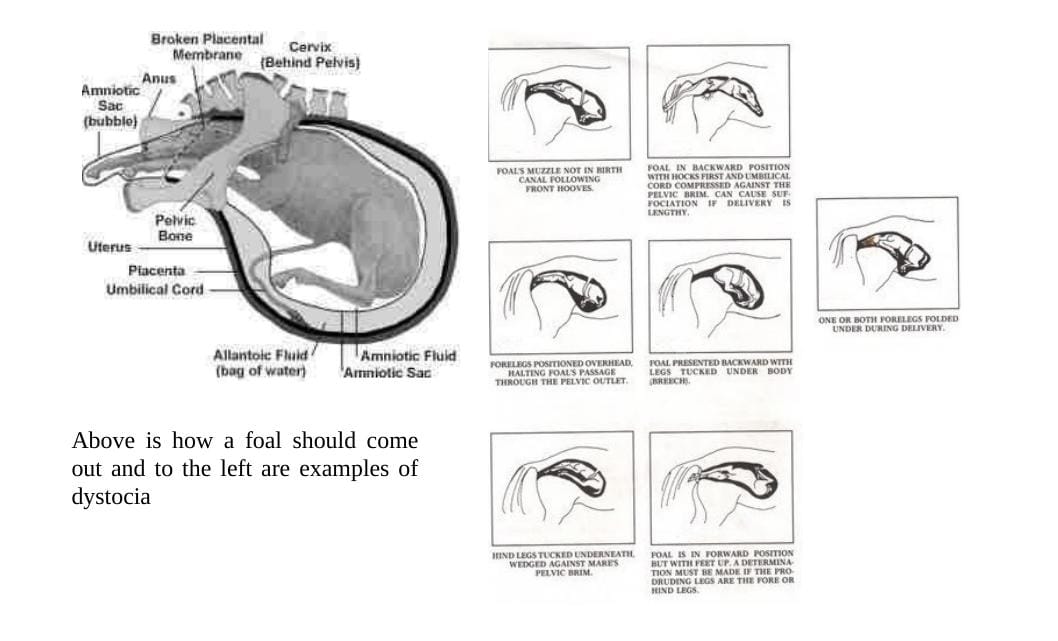

Under normal circumstances, after the water breaks the first part of the placenta, the amnion (“the bubble”), will be visible within 20 minutes and it should be a semi-opaque whitish colour. At this point, I may put on the surgical glove and reach into the vagina to feel for the two front legs and head. The proper position for a foal coming out is front legs and head first out with the head lying on top of the legs. The helper will hold the mare’s head while I do this if the mare is not lying down or simply remain on hand with a maiden mare in case she kicks.

If the placenta presents as red, not white, this is called a “red bag”. Basically this means that the placenta detached from the uterus wall. This is bad because it means that the foal has been without oxygen for an unknown number of minutes. *** A 'red bag' delivery is an emergency that requires immediate veterinary intervention. While tearing the bag and assisting delivery may save the foal, this should only be attempted if a qualified professional cannot arrive in time.

It happened once that, at the forty minute mark after a mare’s water breaking, the mare was not showing the placenta bubble and I couldn’t feel the foal’s front legs and head. The vet had to be called immediately, and the mare taken out of the box and kept walking until the vet arrived (as though she were in the middle of a bad colic) – the walking stopped her from trying to foal and may have helped her turn the foal around because, I later found out, it was trying to come out upside down (the proper term for a foal coming out incorrectly is dystocia).

*** If the foal is not presenting correctly, it is crucial to call a veterinarian immediately. Attempting to reposition the foal without proper training can cause serious harm to the mare and foal.

The mare may get up and lie down several times and roll to get the foal into the right position and she may lie down eventually and start to push. Once the front legs start to present themselves, you should be present to ensure that things continue to progress smoothly (for example, the foal may accidentally put a foot through the vaginal canal and into the rectum – this only takes a hand on the foal's foot to guide it out and pull the vulva out of the way to avoid). If the mare lies down but doesn’t start pushing, I may give the foal’s leg a bit of a wiggle to encourage the pushing reflex.

Most births can happen without human interference, but occasionally some help will be required. For example, if the foal is big the mare might have trouble getting the shoulders out and someone will have to break open the white amnion of the placenta and pull the front legs to get it out. If I do have to pull, it’s important to remember to pull at a slightly downward angle (towards the mare’s feet) rather than straight out.

Once the front legs are mostly out and the head is starting to show, I break the bag and peel it away from the foal as it comes out. Once the shoulders are out the rest will follow much more easily, back legs last of all.

If the mare has been lying down, the umbilical cord usually detaches as she stands and turns to her foal. Or if she has birthed standing, it may detach quickly as the foal falls to the floor. Where it was attached to the foal (the belly button!), it may bleed. If this is the case, it may need to be held tight to the body of the foal until it stops. This is to help it seal properly and to prevent, especially in the case of a colt, a redirection and leaking of urine through the wound. If the umbilical cord does not detach properly or continues to bleed heavily, I would immediately contact the vet to avoid any complications.

Once the bleeding of the navel has stopped, iodine can be applied using a gloved hand. The glove is important because it reduces the risk of infection to the foal but also because it could burn your skin (as well as stain everything it comes in contact with!).

Some mares may need encouragement to bond with the foal and help her realise that she’s given birth (especially with maiden mares, who, after the trauma of birth often don’t understand what has actually happened). If this is the case, the foal can be moved to her head. She should start licking the foal and “talking” to it.

The warmed enema may then be given to the foal to help it pass its first droppings (also called “meconium”) and the placenta (“afterbirth”) should be tied up. You want it to come out naturally and as a whole.

*** Enemas should be used sparingly and only under the advice of a veterinarian, as improper use can cause harm to the foal

The cold water can be used over the foal’s ears to help them clear fluids and at this point, all going well, your helper can then go back to bed!

Notes to take from foaling:

- The time of birth.

- Whether it was an easy foaling.

- Colour and gender (where I work we have a code for this: B = bay; Br = brown; Ch = chestnut and C = colt or F = filly. So a code with “BF” means “bay filly”).

- Time that the afterbirth was passed and if it was intact or not. *More on this later.

- The time the foal passed meconium - This is important because it means the foal’s plumbing is working – if it’s not the foal might colic and the vet would have to be called.

- The time the foal was first standing.

- The time the foal was first drinking.

- The time the foal went to sleep for the first time again.

The next part is a bit of a waiting game...

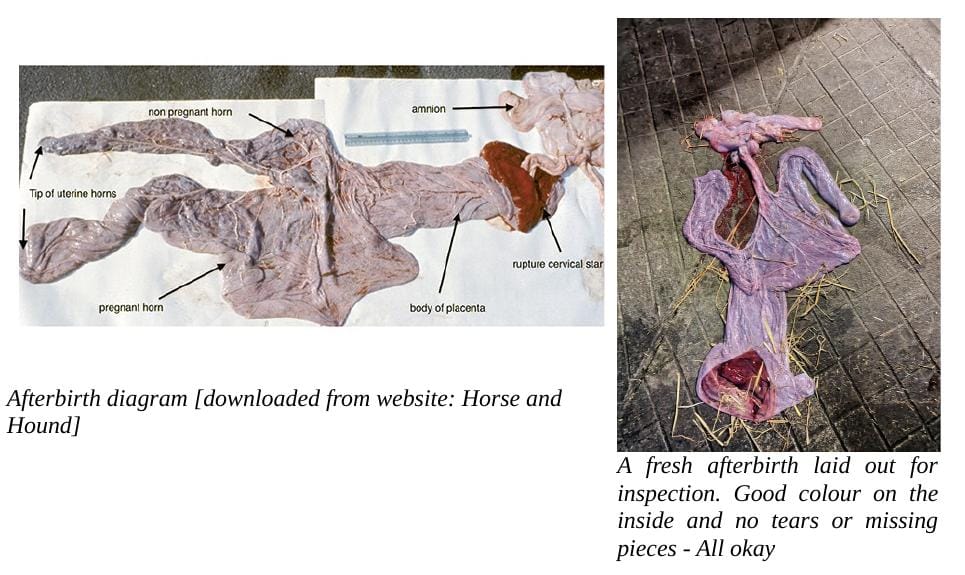

I need to wait for the afterbirth to pass, which could take anywhere from 15 minutes to an hour. Staying close at this time is required because if the afterbirth passes and is left in the stable there’s a chance the mare will try to eat it (or otherwise damage it).

On inspection, the afterbirth should have a good red colour on the inside. Other colours such as “mealy” could indicate an infection of the placenta. If the afterbirth is torn or missing pieces the vet will have to be called to clear it out of the mare and the mare is more likely to colic in the hours following birth. Small tears could happen through weight when the afterbirth is lifted and should be noted.

*** If any abnormalities are found in the afterbirth (e.g., discolouration, tears, or retained pieces), consult a veterinarian immediately to ensure the mare’s health and prevent complications.

The Foal:

I usually give the foal up to an hour and a half after birth to stand. If they can’t figure out how or are having trouble, I’ll go in to help. This usually means that I position the front legs out in front of them and then run a hand down their spine to encourage them to engage their back legs. It may take them a few tries to stay up and sometimes I can help them with that too. The important thing to note here is that I do not want the foal to rely on me to push them up or they’ll never learn to balance and stand themselves. So I’ll avoid bracing them up. Standing is their job. I’m just the cheerleader and/ or coach on the sidelines.

Once they’re standing, I’ll give them another 30-50 minutes to drink. An experienced mare won’t usually need a human’s help for this, but young mares and maidens sometimes have trouble. They don’t know to stand still or they’re ticklish and knock the foal away (not good) or they’re extra protective and want a nose on the foal at all times. Sometimes they just can’t figure out how to encourage their new baby to drink!

A new mare will probably need to be held (a clip-on lead rope is enough usually), but unless the mare is aggressive towards the foal (in which case they’ll need a mediator until the mare settles), a human should stay out of the way until the foal is ready to drink (the sucking reflex kicks in).

A newborn may make a sucking face and lick the walls, their mother, themselves, but until their sucking reflex starts there’s nothing that can be done. Once the foal’s sucking reflex kicks in, they can be guided under the mare. If I’m needed, I’ll position the foal and then move to the opposite side of the mare and touch the foals lips and tongue so that they follow my fingers to the teat. This doesn’t always work. And you need a few tries and patience or to just stand there and watch until licking becomes sucking and sucking becomes swallowing. Once you hear/ see the foal swallow, you know you’re all good because the foal understands where the food comes from and how to get it. A foal will drink until it’s not thirsty/ hungry and then lie down.

If a foal has not drunk by the end of three and a half hours after birth at the absolute latest, it will need to be bottle fed, because it will start to get weak the longer it doesn’t feed – most of its energy was used in standing up the first time. It may also need to bottle feed if the mare has been running milk for days prior to birth because the best of the nutrient-rich colostrum will be gone.

If a foal is not lying down again, but getting tired (wobbly legs, sleepy looking and looking like it’s trying to lie down), I may help – this usually only happens with big foals and it’s because they’re afraid of the fall. All this means is lifting it around the chest and under the buttock and sweeping the legs out from under it. Once they’ve gone down once, they’re usually okay after that.

A foal should get up again after 20-30 minutes to drink for the first few hours after birth, but within the first 24 hours, this usually dwindles to once an hour which is enough.

On the mare's part, in the early hours, I watch for things like colic or internal bleeding. Also instead of standard hard feed, the mare would get a mash in the morning and for the next couple of meals.

For the morning handover to the day shift, I would summarise the rest of the night - “foal drinking both sides and sleeping regularly” or “foal drinking, but only one side and sleeping regularly" and basically anything else of note with both of them. They will continue to monitor, note any relevant observations and be on hand should there be a deterioration in either.

Hopefully, from here though, it's simply continuing to let nature take its course and enjoying watching the Mum and Baby bond after what has been a long but beautiful night.

Disclaimer:

This article is intended for informational purposes only. It is not a substitute for professional veterinary advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Equitas and the author have made every effort to provide accurate and reliable information, but are not liable for any outcomes resulting from the application of this content. Always consult a qualified veterinarian for guidance in foaling and related medical procedures. Additionally, all external sources and images have been credited where applicable; any use beyond fair use is the responsibility of the reader to verify.

Bibliography

- https://veteriankey.com/the-mare/

- https://www.quora.com/How-does-a-foal-come-out-of-a-horse

- https://www.horseandhound.co.uk/plus/equine-placenta-vital-information-need-know-hh-vip-532410

- Pozor, M. (2016), Equine placenta – A clinician's perspective. Part 1: Normal placenta – Physiology and evaluation. Equine Vet Educ, 28: 327-334. https://doi.org/10.1111/eve.12499

- Rossdale, P. D. (1993). The horse from conception to maturity: A textbook for Horse Breeders & Students Taking NPS, BHS & NVQ Examinations. J.A. Allen & Company Limited.

- Photos: Those taken from external sources are credited above, but some were taken by the author